| Solar Storm spotted by Spacecraft |

Originaltext von der NASA

Donald Savage Headquarters, Washington, DC April 9, 1997 (Phone: 202/358-1547)

Jim Sahli Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD (Phone: 301/286-0697)

Barbara McGehan NOAA, Boulder, CO (Phone: 303/497-6288)

RELEASE: 97-67

A large eruption on the Sun was detected at 10 a.m. EDT, on Monday, April 7 by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft, and scientists say the ejected matter, traveling through space as a so-called interplanetary magnetic cloud, is likely to reach the Earth at 8 p.m. EDT today. The storm is large in size; however, it is moderate in strength compared to many others that have reached the Earth in the past.

Although the SOHO findings are of interest to scientists, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Space Environment Center (SEC), provider of official government forecasts, has predicted, based on "e;classical indicators,"e; that the solar storm will be an ordinary event and pose no danger to the population at large.

SEC notes the absence of energetic solar particles which would be expected to accompany a strong solar storm. Such particles, if present, can increase radiation levels for astronauts and cosmonauts in orbit. "e;We are forecasting an event with conditions below the threshold of concern for most of our users,"e; said Dr. Ernie Hildner, head of the Space Environment Center.

The center of the storm will miss the Earth, but it could be broad enough to affect the Earth's space environment and could cause increased auroral activity (Northern and Southern lights) at high latitudes. In the past, some solar storms have affected spacecraft in orbit, shortwave communications and electric power grids.

SOHO, a joint project of NASA and the European Space Agency, is positioned about 900,000 miles sunward of the Earth. The spacecraft has a continuous telescopic view of the Sun and also is equipped with sensors to sample solar particles as they sweep past. A vast network of satellites, space probes, and ground sensors, part of the International Solar Terrestrial Physics (ISTP) program, is monitoring the approaching interplanetary storm and preparing to observe its possible effects on the Earth's space environment.

The solar eruption, called a coronal mass ejection, was first spotted by Shane Stezelberger, a ground controller with SOHO's Large Angle Coronagraph and Spectrometer (LASCO) team at the SOHO Experiment Operations Facility at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD. "I knew it was a big one when I saw it," said Stezelberger, a recent graduate of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg. He promptly notified SOHO scientists, including Dr. Barbara Thompson, whose immediate reaction was "Wow." Dr. Donald Michels of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory said, "We've never before seen one headed directly at Earth that was as big and bright, and loaded with complex details, as this one." SOHO was launched on Dec. 2, 1995.

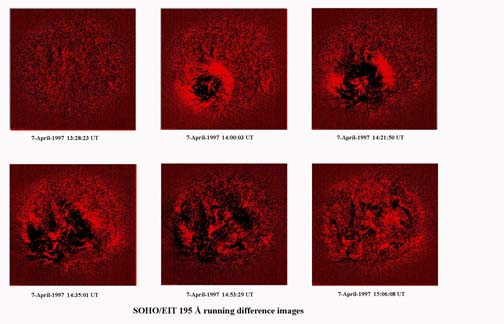

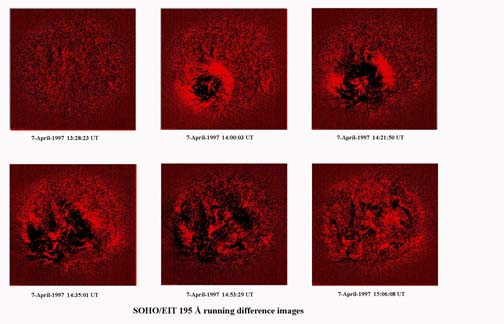

"The eruption seemed to blow open a hole in the Sun's corona that had opened and then healed previously," said Dr. Thompson, who is a physicist with SOHO's Extreme-Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT) team. Accompanying the coronal mass ejection was a powerful solar flare explosion, according to Dr. Arthur Poland, NASA's SOHO Project Scientist. "The flare triggered a supersonic wave that swept through the corona like a tsunami on the surface of the sea," Dr. Poland said.

A sensor called the WAVES experiment on NASA's WIND satellite, positioned near the SOHO, detected bursts of radio emissions from high speed electrons associated with the explosion, also beginning at about 10 a.m. EDT Monday.

The interplanetary storm, traveling toward Earth at a speed of over 1,500,000 miles per hour, is expected to pass the WIND and SOHO satellites at about 7 p.m. EDT Wednesday, and to strike the Earth's magnetosphere an hour later, according to Dr. Nicola Fox, Global Geospace Science program coordinator at Goddard. At that time, according to her projections, the Geotail satellite, a joint Japanese-NASA spacecraft that is part of the ISTP program, will be passing through the center of the Earth's magnetic tail, on the side opposite the Sun. "Geotail will be ideally positioned to observe storm activity like dipolarizations and bursty bulk flows of plasma," she added. Plasma is the scientific term for electrified gas.

NASA's Earth-orbiting POLAR satellite will train its battery of visible, ultraviolet and X-ray cameras on the north and south polar regions of the Earth to observe "a likely considerable enhancement of the aurora," said Dr. Robert Hoffman, POLAR Project Scientist. And, with other POLAR onboard sensors, "we'll look for possible large increases in the intensity of the radiation belts." The likely impact of the interplanetary cloud on the magnetosphere could be to compress it, driving the radiation belts closer to the Earth, as occurred in January after a smaller coronal mass ejection lifted off the Sun on Jan. 6.

Analysis of the spacecraft and ground sensor data on this week's solar storm and its effects on the Earth should lead to a better understanding of the basic physical processes involved and how such disturbed conditions of "space weather" can be predicted.

Spectacular images of this solar storm from SOHO's LASCO and EIT instruments are available from Goddard Public Affairs at 301/286-0697. The images also are available on the internet at:

| 3.11.1997 |